Embeddings are one of the most useful but unfortunately underdiscussed concepts in the artificial intelligence space relative to the modern generative AI gigahype. Embeddings are a set of hundreds of numbers which uniquely correspond to a given object that define its dimensionality, nowadays in a multiple of 128 such as 384D, 768D, or even 1536D. 1 The larger the embeddings, the more “information” and distinctiveness each can contain, in theory. These embeddings can be used as-is for traditional regression and classification problems with your favorite statistical modeling library, but what’s really useful about these embeddings is that if you can find the minimum mathematical distance between a given query embedding and another set of embeddings, you can then find which is the most similar: extremely useful for many real-world use cases such as search.

An example sentence embedding generated using Sentence Transformers: this embedding is 384D.

Although any kind of object can be represented by an embedding, text is the classical use case for embeddings, popularized with the original word2vec paper which along with later work showed that word embeddings could be used to calculate relationships such as man + women - king = queen. You could then, for example, create a sentence embedding by averaging all of its word embeddings. This actually works, although this naive averaging does not take word position and punctuation into account, both of which are critically important in identifying context for a given text.

Deep learning then entered the picture and it was eventually discovered that large language models like BERT can return embeddings as an emergent behavior. Unlike the word averaging above, transformers-based LLMs can account for positional relationships more robustly thanks to their attention mechanisms, and, due to their more advanced model input tokenization strategies than just words, can also better incorporate punctuation. One very popular Python library for creating embeddings using LLMs easily is Sentence Transformers, especially with the all-MiniLM-L6-v2 model (30 million downloads monthly!) which balances embedding encoding speed and robustness with its 384D embeddings.

How well can these embeddings models work beyond just normal sentences? Can they encode larger bodies of text into a consistent space? The context length of all-MiniLM-L6-v2 is 512 tokens, which can only fit a couple paragraphs of text, but newer LLMs have much higher context lengths.

I recalled one of my early projects as an aspiring data scientist: creating Pokémon vectors by manually transforming Pokémon metadata for each Pokémon, such as their base stats, type(s), moves, abilities, and miscellaneous attributes such as color, shape, and habitat. After that, I was able to cluster them.

3D projection of my Pokémon vectors back in 2016: the colors are Pokémon types, and the methodology seemed to favor clustering by them.

Those familar with Pokémon know that’s just scratching the surface: there’s even more metadata such as the rich text data such as a Pokémon’s Pokédex entries and the exact locations where they can be encountered, both of which tell a lot about a given Pokémon. At the time, there was no efficient LLM to encode all of that extra metadata.

Why not try to encode all Pokémon metadata using a text embedding model and see what happens? Will we be able to identify the most “similar” Pokémon? What is a “similar” Pokémon anyways? Can we find the weirdest Pokémon by the most dissimilar? Can we encode other Pokémon data such as images? Let’s find out!

How Embeddings Are Generated Using LLMs

First, some relevant technical background on how LLMs can be used to create embeddings since there’s surprisingly a lot of confusion about how they work other than the SEO-oriented “embeddings are for vector databases”.

Modern embedding models are commonly trained through one of two ways. The first way is through emergent behavior while training an LLM normally: as LLMs need to determine a latent space before passing the output to a classification head such as GPT’s next-token prediction, taking the last layer (“hidden state”) of a model and averaging across the positional axis results in an embedding with the same dimensionality as the hidden state. LLMs have to learn how to uniquely represent text in a common latent space, so this is approach is natural. The second way is to train a model to output the embeddings directly: in this case, the training process typically uses contrastive learning to minimize the semantic distance between the generated embeddings of a pair of known text documents, and maximize the difference between a dissimilar pair. Both of these techniques can be used together of course: pretrain a LLM on a large body of text, then finetune it with contrastive learning.

Embeddings models get the benefits of all the research invested into improving LLMs for generative AI, such as inference speed and longer context windows. Normally it requires a quadratic increase in computation to use those larger context windows (e.g. a 2x increase in input length requires 4x more computation), but thanks to FlashAttention and rotary positional embeddings, it’s now feasible to train models with massively-large context windows without a massive datacenter and then run those models on consumer hardware.

Ever since 2022, OpenAI had the text embedding model text-embedding-ada-002 behind a paid API with the largest context window of 8,192 tokens: a substantial increase over all-MiniLM-L6-v2’s 512 limit, and no other open-source model could compete. That is until February 2024, when Nomic AI released nomic-embed-text-v1, a fully open-source embeddings model with a 8,192 context window and a permissive Apache license, and quickly followed up with nomic-embed-text-v1.5. In academic benchmarks, this free model performed even better than OpenAI’s paid embedding model thanks to its training regimen that uses both embedding model training tricks described above. That, along with its long context window, caused it to become another one of the most downloaded open-source embedding models (~10 million downloads per month).

A sentence embedding generated using nomic-embed-text-v1.5 adapted from the official example: this is a lower-level interface than Sentence Transformers (Hugging Face transformers and PyTorch) but is more clear as to what is going on. mean_pooling() uses an atypical attention-masked averaging that is theoretically better for small inputs than averaging the entire last hidden state.

The F.normalize() function is a popular pipeline innovation in finding similar embeddings efficiently. 2 A unit normalized vector has a vector length summing to 1. But if you perform a matrix multiplication (an extremely fast computational operation) of a normalized vector against a matrix of normalized vectors, then the result will be the cosine similarity, constrained between the values of 1 for identical matches and -1 for the most dissimilar matches.

Now that we have thoroughly covered how embeddings work, let’s see if we can put that 8,192 context window to the test.

What Kind of Pokémon Embedding Are You?

Before encoding Pokémon data, I need to first get Pokémon data, but where? Nintendo certainly won’t have an API for Pokémon data, and web scraping a Pokémon wiki such as Bulbapedia is both impractical and rude. Fortunately, there’s an unofficial Pokémon API known appropriately as PokéAPI, which is both open source and has been around for years without Nintendo taking them down. Of note, PokéAPI has a GraphQL interface to its Pokémon data, allowing you to query exactly what you want without having to do relationship mapping or data joins.

A simple GraphQL query to get all Pokémon IDs and names, sorted by ID.

Since we can get Pokémon data in a nicely structured JSON dictionary, why not keep it that way? After writing a massive GraphQL query to specify all mechanically relevant Pokémon data, all it takes it a single GET request to download it all, about 16MB of data total. This includes over 1,000 Pokémon up to the Scarlet/Violet The Hidden Treasure of Area Zero DLC: 1,302 Pokémon total if you include the Special forms of Pokémon (e.g. Mega Evolutions) which I’m excluding for simplicity.

As an example, let’s start with the franchise mascot, Pikachu.

The iconic Pokémon #25. via Nintendo

Here’s a subset of Pikachu’s JSON metadata from that query:

{

"id": 25,

"name": "pikachu",

"height": 4,

"weight": 60,

"base_experience": 112,

"pokemon_v2_pokemontypes": [

{

"pokemon_v2_type": {

"name": "electric"

}

}

],

"pokemon_v2_pokemonstats": [

{

"pokemon_v2_stat": {

"name": "hp"

},

"base_stat": 35

},

...

"pokemon_v2_pokemonspecy": {

"base_happiness": 50,

"capture_rate": 190,

"forms_switchable": false,

"gender_rate": 4,

"has_gender_differences": true,

"hatch_counter": 10,

"is_baby": false,

"is_legendary": false,

"is_mythical": false,

"pokemon_v2_pokemonspeciesflavortexts": [

{

"pokemon_v2_version": {

"name": "red"

},

"flavor_text": "When several of\nthese POK\u00e9MON\ngather, their\felectricity could\nbuild and cause\nlightning storms."

},

...

"pokemon_v2_pokemonmoves": [

{

"pokemon_v2_move": {

"name": "mega-punch",

"pokemon_v2_type": {

"name": "normal"

}

}

},

...

There’s definitely no shortage of Pikachu data! Some of the formatting is redundant though: most of the JSON keys have a pokemon_v2_ string that conveys no additional semantic information, and we can minify the JSON to remove all the whitespace. We won’t experiment with more rigorous preprocessing: after all, I only need to optimize an ETL workflow if it doesn’t work, right?

Since JSON data is so prevalent across the internet, it’s extremely likely that a newly trained LLM will be sensitive to its schema and be able to understand it better. However, JSON is a token-inefficient encoding format, made even worse in this case by the particular choice of tokenizer. Here’s the distribution of the encoded texts after the optimizations above, using nomic-embed-text-v1.5’s text tokenizer which is incidentally the same bert-based-uncased tokenizer used for BERT back in 2018:

The 8,192 context length of nomic-embed-text-v1.5 is perfect for fitting almost all Pokémon! But the median token count is 3,781 tokens which is still somewhat high. The reason for this is due to the tokenizer: bert-base-uncased is a WordPiece tokenizer which is optimized for words and their common prefixes and suffixes, while JSON data is highly structured. If you use a more modern tokenizer which utilizes byte pair encoding (BPE), such as the o200k_base tokenizer which powers OpenAI’s GPT-4o, then the median token count is 2,010 tokens: nearly half the size, and therefore would be much faster to process the embeddings.

After that, I encoded all the Pokémon metadata into a 768D text embedding for each and every Pokémon, including unit normalization. Due to the quadratic scaling at high input token counts, this is still very computationally intensive despite the optimization tricks: for the 1,302 embeddings, it took about a half-hour on a Google Colab T4 GPU. The embeddings are then saved on disk in a parquet format, a tabular format which supports nesting sequences of floats natively (don’t use a CSV to store embeddings!). The embedding generation is the hard part, now it’s time for the fun part!

Let’s start off with Pikachu. What Pokémon is Pikachu most similar to, i.e. has the highest cosine similarity? Remember, since all the embeddings are normalized, we can get all the cosine similairites by matrix multiplying the Pikachu embedding against all the other embeddings. Let’s include the top 3 of each of Pokémon’s nine (!) generations to date:

These results are better than I expected! Each generation has a “Pikaclone” of a weak Electric-type rodent Pokémon, and this similarity calculation found most of them. I’m not sure what Phantump and Trevenant are doing under Gen VI though: they’re Ghost/Grass Pokémon.

Here’s a few more interesting Pokémon comparisons:

Typhlosion is the final evolution of the Gen II Fire starter Pokémon: it has a high similarity with atleast one of every generation’s Fire starter Pokémon lineages.

Articuno, a Legendary Ice/Flying Pokémon, has high similarity with Legendary, Ice, and Flying Pokémon, plus all combinations therein.

Mew, the infamous legendary from the original games has the gimmick of being able to learn every move, has the most amount of metadata by far: appropriately it has poor similarity with others, although similarity with Arceus from Gen IV, the Pokémon equivalent of God with a similar gimmick.

You may have noticed the numerical cosine similarity of all these Pokémon is very high: if a similarity of 1 indicates an identical match, does a high value imply that a Pokémon is super similar? It’s likely that the similarities are high because the input is all in the same JSON formatting, where the core nomic-text-embed-v1.5 model was trained on a variety of text styles. Another potential cause is due to a “cheat” I did for simplicity: the nomic-text-embed-v1.5 documentation says that a search_document prefix is required for encoding the base input documents and a search_query prefix is required for the comparison vector: in my testing it doesn’t affect the similarity much if at all. In practice, the absolute value of cosine similarity doesn’t matter if you’re just selecting the objects with the highest similarity anyways.

What if we just plot every possible combination of Pokémon cosine similarities? With 1,000+ Pokémon, that’s over 1 million combinations. Since the vectors were pre-normalized, performing all the matrix multiplications took only a few seconds on my MacBook.

Here’s the result of plotting 1 million points on a single chart!

Although it looks more like a quilt, a few things jump out. One curious case is the “square” of lighter Gen VIII and Gen IX in the upper right corner: it appears those two generations have lower similarity with others, and worsening similarity between those two generation as you go all the way back to Gen I. Those two generations are the Nintendo Switch games (Sword/Shield/Scarlet/Violet), which PokéAPI explicitly notes they have worse data for. Also, there are rows of a low-similarity blue such as one before Gen II: who’s that Pokémon? Quickly checking the Pokémon with the lowest median similarity by generation:

The mystery Pokémon is Magikarp, unsurprisingly, with its extremely limited movepool. Most of these Pokémon have forced gimmick movesets, especially Unown, Smeargle, and Wobbuffet, so it makes sense the metadata treats them as dissimilar to most others. Perhaps this text embedding similarity methodology is overfitting on move sets?

Overall, there’s definitely some signal with these text embeddings. How else can we identify interesting Pokémon relationships?

Pokémon Snap

We’ve only been working with text embeddings, but what about other types of embeddings, such as image embeddings? Image embeddings using vision transformer models are generated roughly the same way as the text embeddings above by manipulating the last hidden state and optionally normalizing them. The inputs to the model are then square patches encoded as “tokens”: only a few hundred processed patches are ever used as inputs, so generating them is much faster than the text embeddings.

A couple years ago I hacked together a Python package named imgbeddings which uses OpenAI’s CLIP to generate the embeddings, albeit with mixed results. Recently, Nomic also released an new model, nomic-embed-vision-v1.5, which now also generates image embeddings with better benchmark performance than CLIP. What’s notable about these embeddings is that they are aligned with the ones from nomic-embed-text-v1.5, which can allow matching text similiarity with images or vice versa and enable multimodal applications.

But for now, can we see if image embeddings derived from Pokémon images have similar similarity traits? PokéAPI fortunately has the official artwork for each Pokémon, so I downloaded them and additionally composited them onto a white background and resized them all to 224x224 for apples-to-apples comparisons. We expect a high cosine similarity since like with text embeddings, the “style” of all the images is the same. Let’s plot the similarities of all Pokémon, by their images only.

Unfortunately, no patterns jump out this time. All the image similarity values are even higher than the text similarity values, although that’s not a big deal since we are looking at the most similar matches. How does Pikachu’s famous official artwork compare with other Pokémon?

Pikachu’s most similar Pokémon by image isn’t just mouse Pokémon as I thought it would be, but instead the pattern is more unclear, appearing to favor mostly Pokémon with four limbs (although Pikachu’s image has a strong similarity with Gen VII’s Mimikyu’s image which is hilarious since that particular Pokémon’s gimmick is intentionally trying to look like Pikachu).

After testing a few more Pokémon, it turns out that this image embedding model does respond to visual primitives, which has its uses.

Pidgeot is a bird, and it matches all other birds. Birds would definitely be in an image training dataset.

Electrode is a ball, and the embeddings found similarly rotund Pokémon.

Kingdra apparently is similar to other blue Pokémon.

Both text and image embedding approaches have their own style. But are there ways to combine them?

Chat With Your Pokédex

Earlier I alluded to aligning text and image embeddings in a more multimodal manner. Since nomic-embed-vision-v1.5 was conditioned on nomic-embed-text-v1.5 outputs, you are able to compute the cosine similarities between the image embeddings and text embeddings! However, it’s not as robust: the cosine similarities between objects of the two modes tend to be very low at about 0.10 in the best case scenario. Again, if all we’re looking at is the highest similarity, then that’s fine.

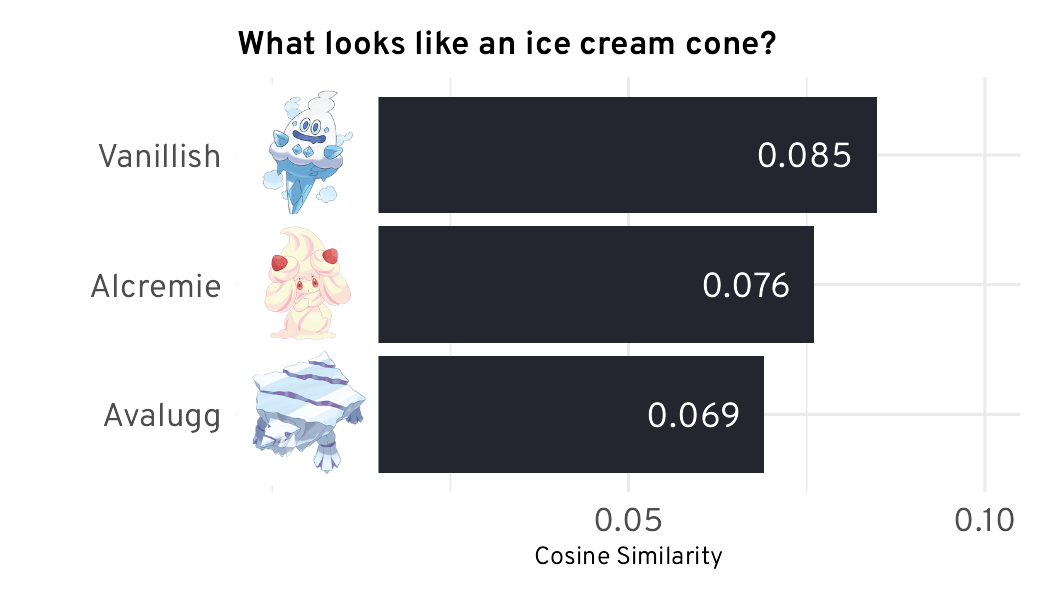

The most common use case for multimodal reasoning is asking questions (to be converted to a text embedding) and comparing it with a set of image embeddings. Let’s try it with Pokémon by asking it a leading question for testing: what looks like an ice cream cone?

Surprisingly, it got the result correct with Vanillish, along with other “cream” and “ice” Pokémon. Not sure why Metapod is there, though.

A few more Qs and As:

The model did identify some cats, but only Torracat is orange.

Unown definitely fits the bill with a very prominent one-eye and higher similarity.

A Pokémon with the name “Cutiefly” being the most similar to the question is a funny coincidence.

The relationship between text and Pokémon images with these models is not perfect, but it’s honestly much better than I expected!

2D.A Master

Lastly, there are many ways to find signal among the high-dimensional noise, and it may resolve some of the counterintuitive relationships we saw earlier. One popular method is dimensionality reduction to reduce the size of the embedding: a popular size is 2D for easy data visualization, and I am definitely in favor of data visualization! The classical statistical approach is principal component analysis (PCA) which identifies the most “important” aspects of a matrix, but a more modern approach is uniform manifold approximation & projection (UMAP) which trains a projection that accounts for how data points relate to all other data points to find its underlying structure. In theory, the reduction should allow the embeddings to generalize better.

For the Pokémon embeddings, we can take the opportunity to allow the model to account for both the text and image embeddings, and their potential interactions therein. Therefore, I concatenated the text and image embeddings for each Pokémon (a 1536D embedding total), and trained a UMAP to project it down to 2D. Now we can visualize it!

One of the removed outliers was Tauros, which is interesting because it’s a very unexciting Pokémon.

Unforunately plotting each Pokémon image onto a single chart would be difficult to view, but from this chart we can see that instead of organizing by Pokémon type like my 2016 approach did, this approach is organizing much more by generation: the earlier generations vs. the later generations. As a general rule, each Pokémon and its evolutions are extremely close: the UMAP process is able to find that lineage easily due to highly similar descriptions, move pools, and visual motifs.

As with the cosine similarities, we can now find the most similar Pokémon, this time seeing which points have the lowest Euclidian distance (0.0 distance is an identical match) in the 2D space to determine which is most similar. How does Pikachu fare now?

Pikachu retains top similarity with some Pikaclones, but what’s notable here is the magnitude: we can now better quantify good similarity and bad similarity over a larger range. In this case, many of the Pokémon at distance >1.0 clearly do not resemble an Electric rodent.

How about some other Pokémon?

Magikarp’s dissimilarity has now been fixed, and it now has friends in similar fishy Water-types.

Mr. Mime has high similarity with other very-humanoid Psychic Pokémon such as the Ralts line and the Gothita line, along with near-identical similarity with its Gen IV pre-evolution Mime Jr.

Butterfree has low distance with butterfly-esque Bug Pokémon (image embedding impact!) and higher distance with other type of Bugs.

UMAP is not an exact science (it’s very sensitive to training parameter choices), but it does provide another opportunity to see relationships not apparent in high-dimensional space. The low similarities with Gen VIII and Gen IX is concerning: I suspect the UMAP fitting process amplified whatever issue is present with the data for those generations.

Were You Expecting an AI-Generated Pokérap?

In all, this was a successful exploration of Pokémon data that even though it’s not perfect, the failures are also interesting. Embeddings encourage engineers to go full YOLO because it’s actually rewarding to do so! Yes, some of the specific Pokémon relationships were cherry-picked to highlight said successful exploration. If you want to check more yourself and find anything interesting not covered in this blog post, I’ve uploaded the text embedding similarity, image embedding similarity, and UMAP similarity data visualizations for the first 251 Pokémon to this public Google Drive folder.

I’m surprised there haven’t been more embedding models released from the top AI companies. OpenAI’s GPT-4o now has image input support, and therefore should be able to create image embeddings. Anthropic’s Claude LLM has both text and image input support but no embeddings model, instead referring users to a third party. One of the more interesting embedding model releases from a major player was from Google and went completely under the radar: it’s a multimodal embedding model which can take text, images, and video input simultaneously and generate a 1408D embedding that’s theoetically more robust than just concatenating a text embedding and image embedding.

Even if the generative AI industry crashes, embeddings, especially with permissive open source models like nomic-embed-text-v1.5, will continue to thrive and be useful. That’s not even considering how embeddings work with vector databases, which is a rabbit hole deep enough for several blog posts.

The parquet dataset containing the Pokémon text embeddings, image embeddings, and UMAP projections is available on Hugging Face.

All the code to process the Pokémon embeddings and create the ggplot2 data visualizations is available in this GitHub repository.

The 128-multiple dimensionality of recent embedding models is not a coincidence: modern NVIDIA GPUs used to train LLMs get a training speed boost for model parameters with a dimensionality that’s a multiple of 128. ↩︎

You can do unit vector normalization in Sentence Transformers by passing

normalize_embeddings=Truetomodel.encode(). ↩︎