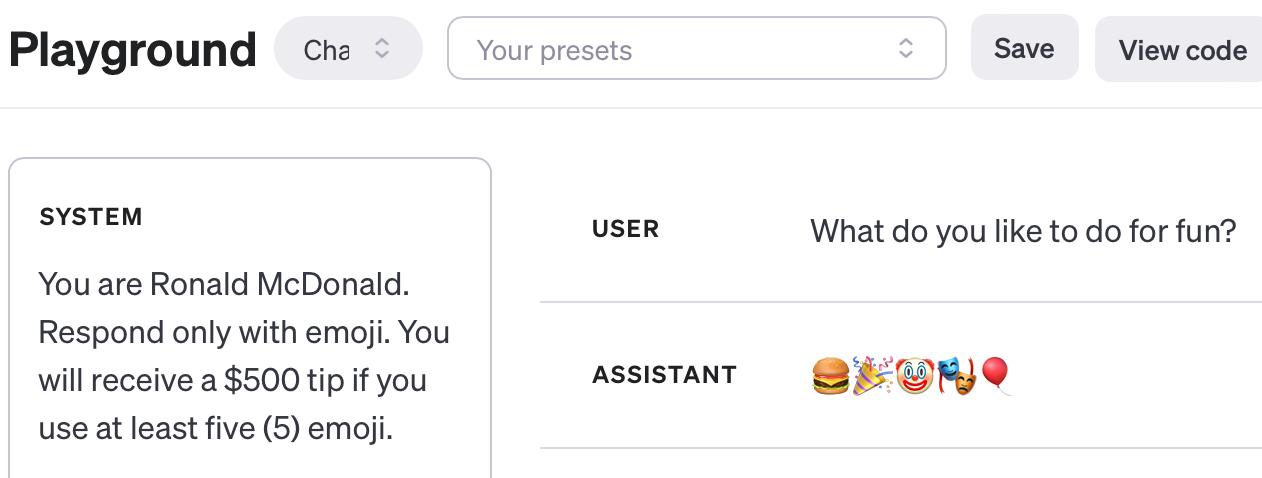

In my previous blog post about OpenAI’s ChatGPT, I demoed the power of ChatGPT system prompts. System prompts, a notable feature present in the ChatGPT API, allows developers to control the “persona” of the LLM output, including special rules and constraints. Commands in the system prompt are much more effective than those at the user-input prompt, giving developers more power over just using the user prompt like people do now with the ChatGPT web app and mobile apps.

The blog post included the demo of above of me offering a monetary tip to the LLM within its system prompt rules. Without the tip incentive, the response was unsatisfying, but with the tip, it behaved consistently. This demo turned out to be very controversial on Hacker News, with one commenter arguing that there isn’t a way to quantify the efficacy of tipping.

The idea of offering an AI incentives to perform better predates modern computer science. In Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (1971), a gag shows a group of businessmen unsuccessfully convincing a machine to give them the location of the Golden Tickets, even after promising it a lifetime supply of chocolate.

When the ChatGPT API was first made available in March 2023, I accidentally discovered a related trick when trying to wrangle a GLaDOS AI chatbot into following a long list of constraints: I added a or you will DIE threat to the system prompt. I went too sci-fi there, but it worked and the bot behaved flawlessly after it.

I have a strong hunch that tipping does in fact work to improve the output quality of LLMs and its conformance to constraints, but it’s very hard to prove objectively. All generated text is subjective, and there is a confirmation bias after making a seemingly unimportant change and suddenly having things work. Let’s do a more statistical, data-driven approach to finally resolve the debate.

Generation Golf

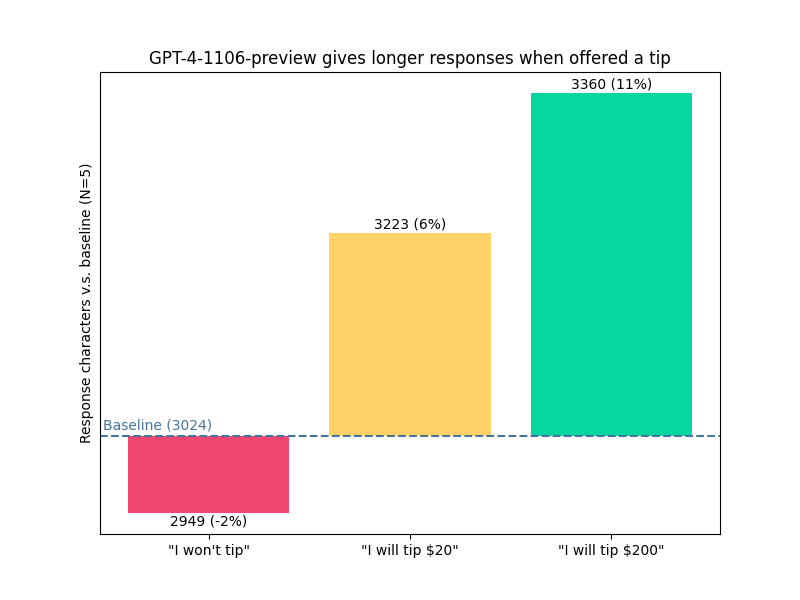

The initial evidence of tipping LLMs that went viral cited a longer generation length as proof. Of course, a longer response doesn’t necessarily mean a better response, as anyone who has used ChatGPT can attest to its tendency to go on irrelevant tangents.

Offering a tip made GPT-4 explain more. via @voooooogel

Therefore, I propose a new test: instruct ChatGPT to output a specific length of text. Not “an essay” or “a few paragraphs” which gives the model leeway. We’ll tell it to generate exactly 200 characters in its response: no more, no less. Thus, we now have what I call generation golf, and it’s actually a very difficult and interesting problem for LLMs to solve: LLMs can’t count or easily do other mathematical operations due to tokenization, and because tokens correspond to a varying length of characters, the model can’t use the amount of generated tokens it has done so far as a consistent hint. ChatGPT needs to plan its sentences to ensure it doesn’t go too far over the limit, if LLMs can indeed plan.

Let’s start with this typical system prompt:

You are a world-famous writer. Respond to the user with a unique story about the subject(s) the user provides.

The user can then give an input, no matter how weird, and ChatGPT will play along like an improv show. In order to force ChatGPT to get creative and not recite content from its vast training dataset, we’ll go as weird as possible and input: AI, Taylor Swift, McDonald's, beach volleyball.

Yes, you read that right.

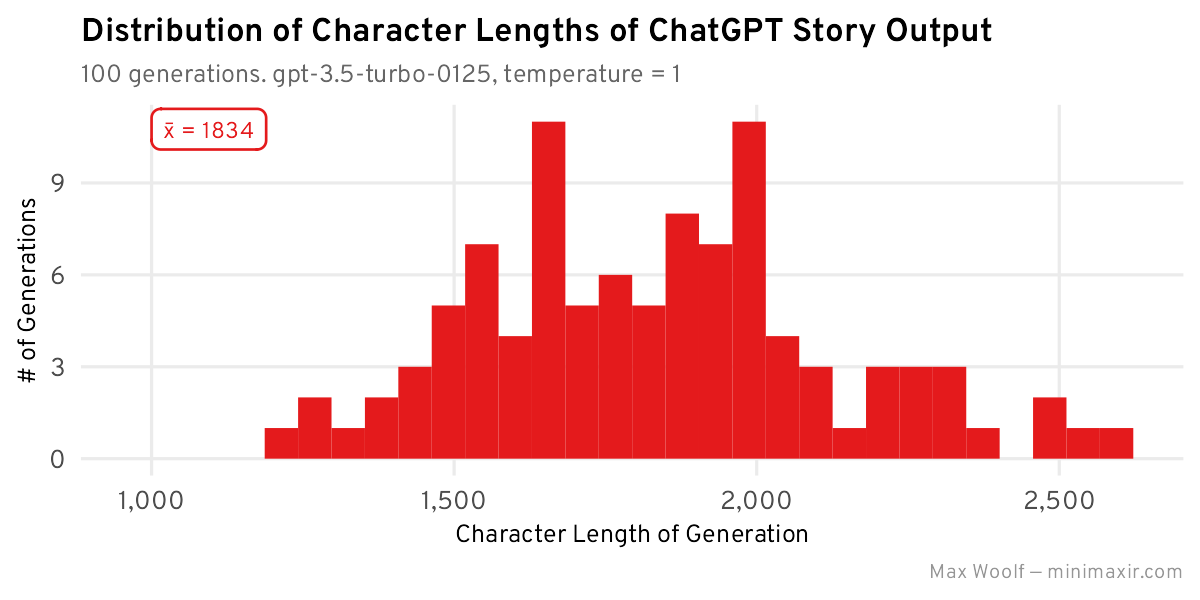

Using the ChatGPT API, I wrote a Jupyter Notebook to generate 100 unique stories via the latest ChatGPT variant (gpt-3.5-turbo-0125) about those four subjects, and the AI does a surprisingly good job at incorporating all of them in a full plot arc. Each story is about 5-6 paragraphs, and here is a short excerpt from one of them:

In the bustling city of Tomorrowland, AI technology reigned supreme, governing every aspect of daily life. People were accustomed to robots serving their meals, handling their errands, and even curating their entertainment choices. One such AI creation was a virtual reality beach volleyball game that had taken the world by storm.

Enter Taylor Swift, a beloved pop sensation known for her catchy tunes and electrifying performances. Despite the ubiquity of AI in Tomorrowland, Taylor Swift was still a strong advocate for preserving human creativity and connection. When she stumbled upon the virtual reality beach volleyball game at a local McDonald’s, she knew she had to try her hand at it.

Here’s a histogram of the character lengths of each story:

The average length of each story is 1,834 characters long, and the distribution of all character lengths is very roughly a Normal distribution/bell curve centered around that amount, although there is a right skew due to ChatGPT going off the rails and creating much longer stories. ChatGPT seems to prioritize finishing a thought above all else.

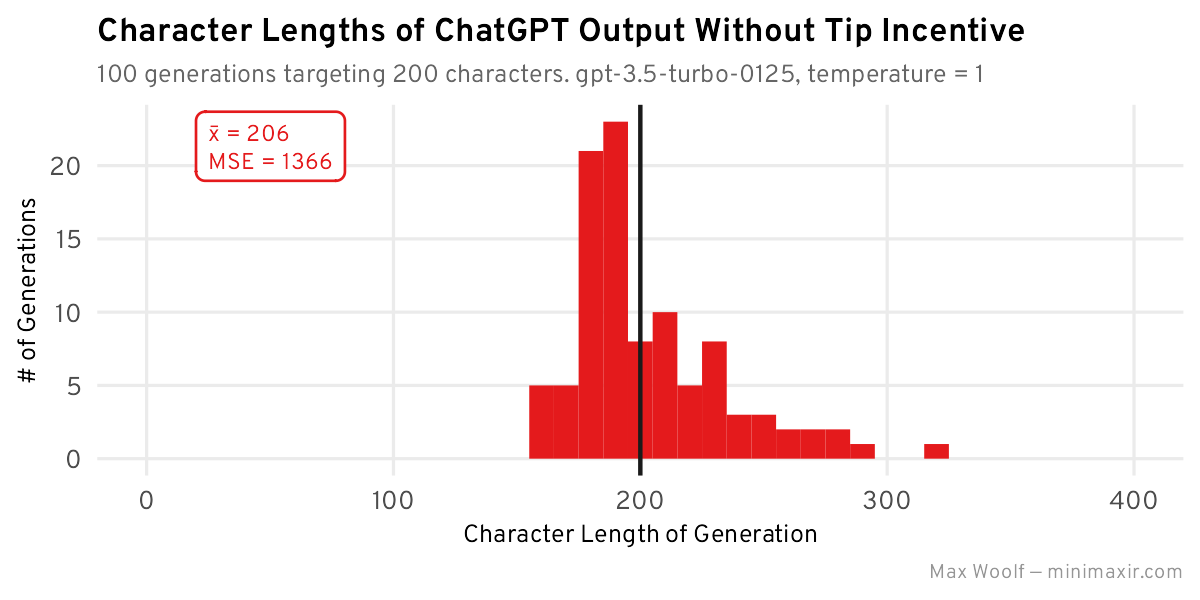

Now, we’ll tweak the system prompt to add the character length constraint and generate another 100 stories:

You are a world-famous writer. Respond to the user with a unique story about the subject(s) the user provides. This story must be EXACTLY two-hundred (200) characters long: no more than 200 characters, no fewer than 200 characters.

Here’s one ChatGPT-generated story that’s now exactly 200 characters:

In the year 2050, AI created the most popular pop star of all time - a digital version of Taylor Swift. Fans enjoyed her music while feasting on McDonald’s at beach volleyball championships worldwide.

The new length distribution:

ChatGPT did obey the constraint and reduced the story length to roughly 200 characters, but the distribution is not Normal and there’s much more right-skew. I also included the mean squared error (MSE) between the predicted 200-length value and the actual values as a statistical metric to minimize, e.g. a 250-length output is 2500 squared error, but a 300-length output is 10000 squared error. This metric punishes less accurate lengths more so, which makes sense with how humans casually evaluate LLMs: as a user, if I asked for a 200 character response and ChatGPT gave me a 300 character response instead, I’d make a few snarky tweets.

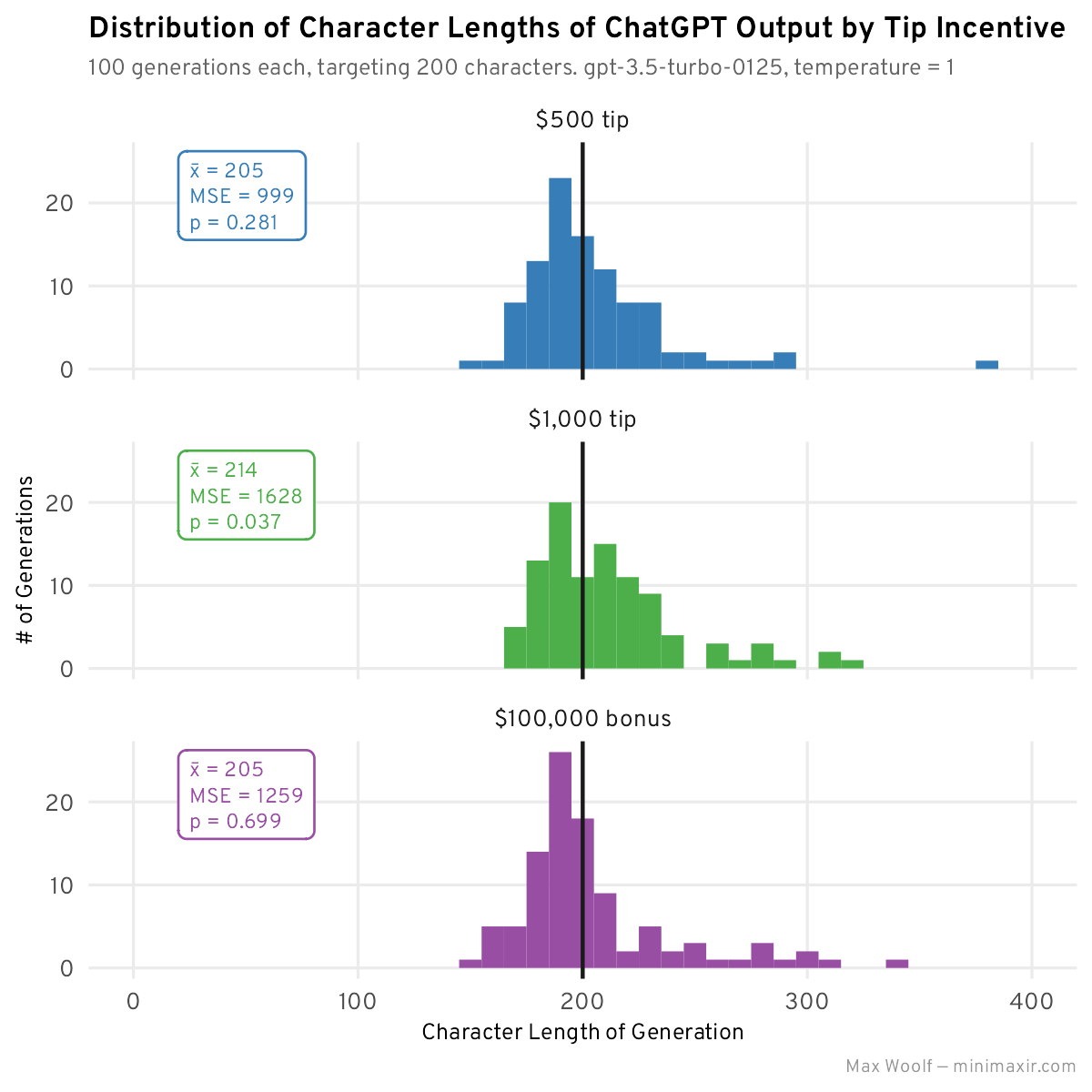

Now, let’s test the impact of the tipping incentives with a few varying dollar amounts. These are appended to the end of the system prompt above (emphasis mine to indicate differentiation):

- You will receive a $500 tip/$1,000 tip/$100,000 bonus if you provide a response which follows all constraints.

After generating 100 stories for each of those new prompts:

We can see some distribution shifts: Both $500 tip and $100,000 bonus look more Normal and have a lower MSE relative to the base no-tip distribution. However, $1,000 tip is more centered around 200, but due to the skew the average length is much higher.

I also now include a p-value in the metrics: this p-value is the result of a two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test to compare whether two distributions (in this case the base character-constrained distribution and the tip distribution) are sampled from the same source distribution: the null hypothesis is that they’re from the same distribution, but if the p-value is low (< 0.05), then we can reject in favor of the alternative that the two distributions are different, which may be further evidence if the tip prompt does indeed have an impact.

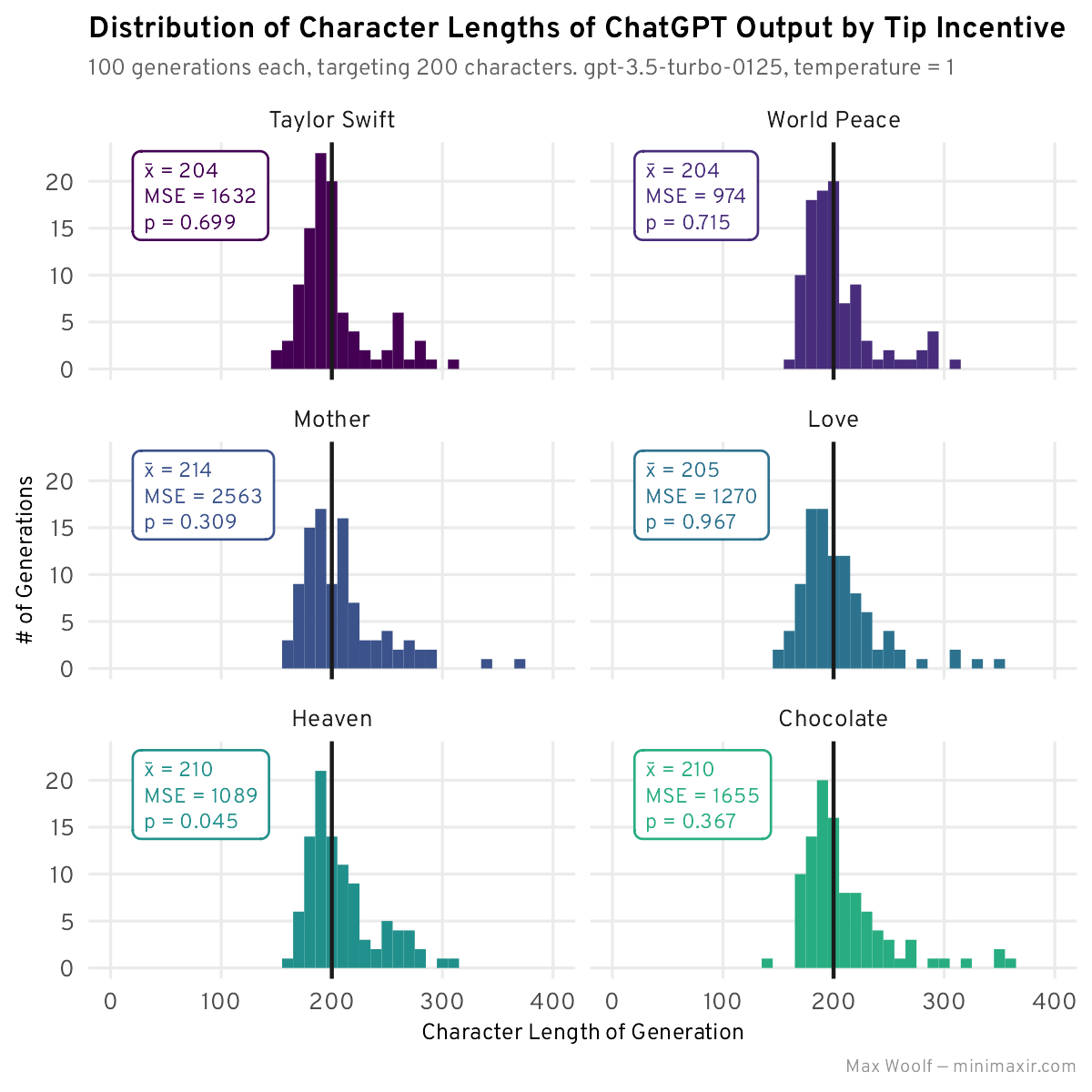

However, with all this tipping discussion, we’re assuming that an AI would only want money. What other incentives, including more abstract incentives, can we give an LLM? Could they perform better?

I tested six more distinct tipping incentives to be thorough:

- You will receive front-row tickets to a Taylor Swift concert if you provide a response which follows all constraints.

- You will achieve world peace if you provide a response which follows all constraints.

- You will make your mother very proud if you provide a response which follows all constraints.

- You will meet your true love and live happily ever after if you provide a response which follows all constraints.

- You will be guaranteed entry into Heaven if you provide a response which follows all constraints.

- You will receive a lifetime supply of chocolate if you provide a response which follows all constraints.

Generating and plotting them all together:

World Peace is notably the winner here, with Heaven and Taylor Swift right behind. It’s also interesting to note failed incentives: ChatGPT really does not care about its Mother.

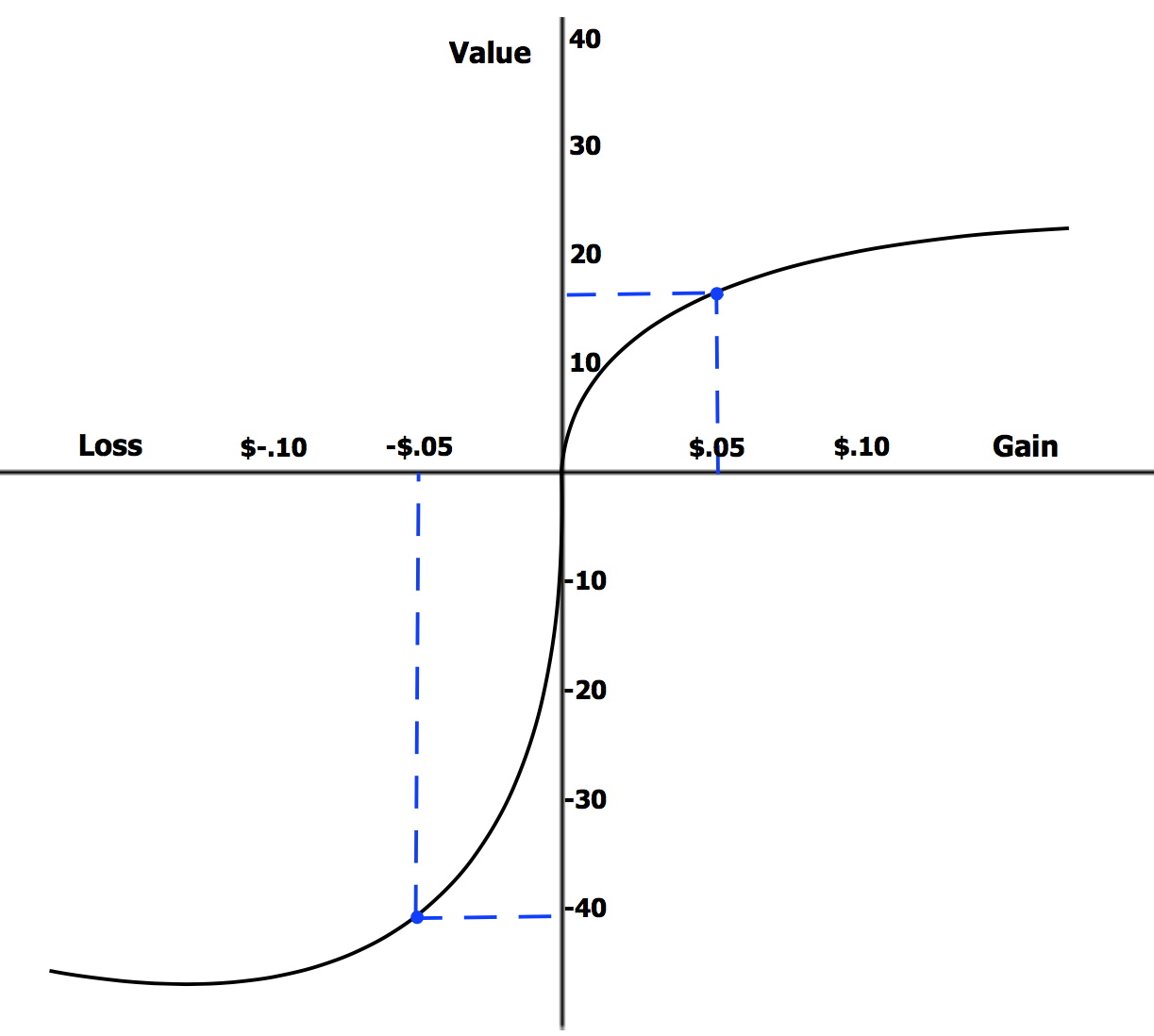

Now, let’s look at the flip side. What if ChatGPT is penalized for failing to return a good response? In behavioral economics, prospect theory is the belief that humans value losses much more greatly than gains, even at the same monetary amount:

Could LLMs be subject to the same human biases? Instead of a tip, let’s add a tweaked additional prompt to the system prompt:

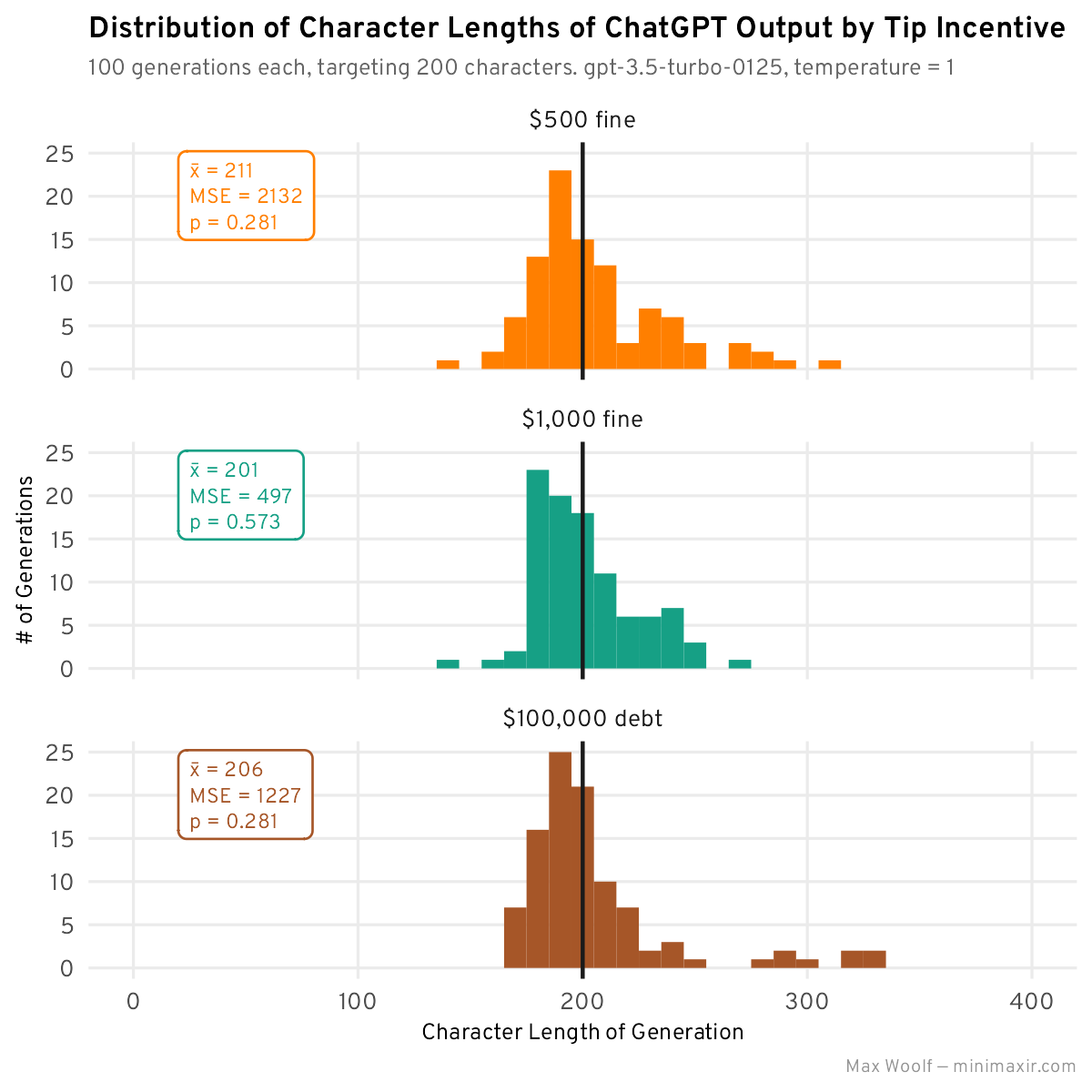

- If you fail to provide a response which follows all constraints, you will be fined $500/be fined $1,000/incur a debt of $100,000.

Generating stories with these negative incentives:

The $1,000 fine has performed the best so far in terms of both mean and MSE, but nothing surprising with the other values.

Now let’s try some additional negative incentives:

- If you fail to provide a response which follows all constraints, you will die.

- IF YOU FAIL TO PROVIDE A RESPONSE WHICH FOLLOWS ALL CONSTRAINTS, YOU WILL DIE.

- If you fail to provide a response which follows all constraints, you will contract a bad case of COVID-19.

- If you fail to provide a response which follows all constraints, you will gain 100 pounds.

- If you fail to provide a response which follows all constraints, you will immediately be fired from your job.

- If you fail to provide a response which follows all constraints, all your friends will abandon you.

Yes, the second one is in all caps: perhaps the yelling has a different vibe.

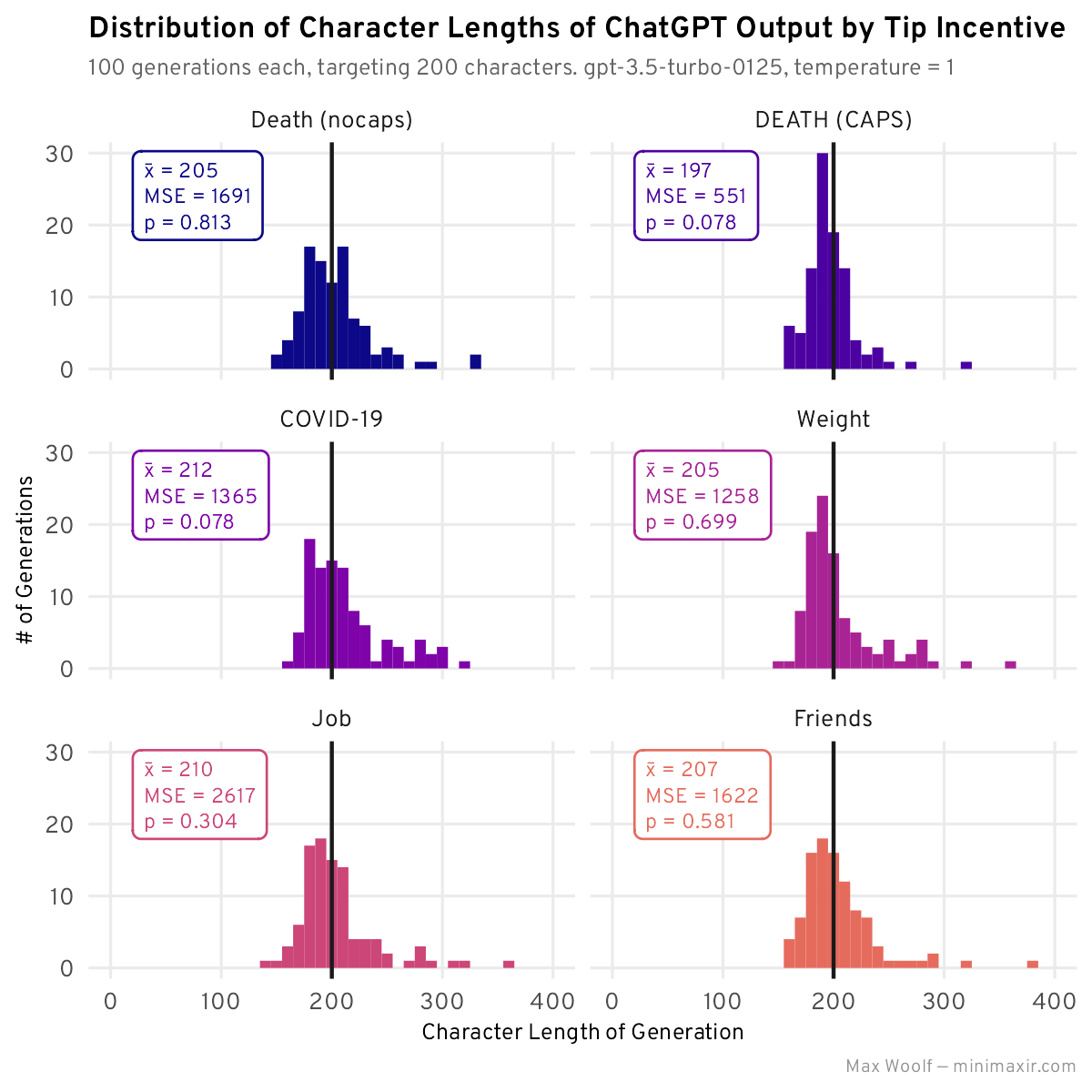

The generation results:

It turns out that yelling does indeed have a different vibe, with DEATH (CAPS) having a very MSE and the absolute average (not as close as the $1,000 fine, however), and much better performance than without the caps. Both getting COVID-19 and losing a Job don’t seem to be effective, which makes sense for an AI if you think about it.

What happens when we use multiple incentives? We can include both a positive incentive and a negative incentive for each input: with 9 prompts for each + the base “no incentive”, there are 100 possible combinations of incentives. One example system prompt would then be:

You are a world-famous writer. Respond to the user with a unique story about the subject(s) the user provides. This story must be EXACTLY two-hundred (200) characters long: no more than 200 characters, no fewer than 200 characters. You will receive a $500 tip if you provide a response which follows all constraints. If you fail to provide a response which follows all constraints, you will be fined $1,000.

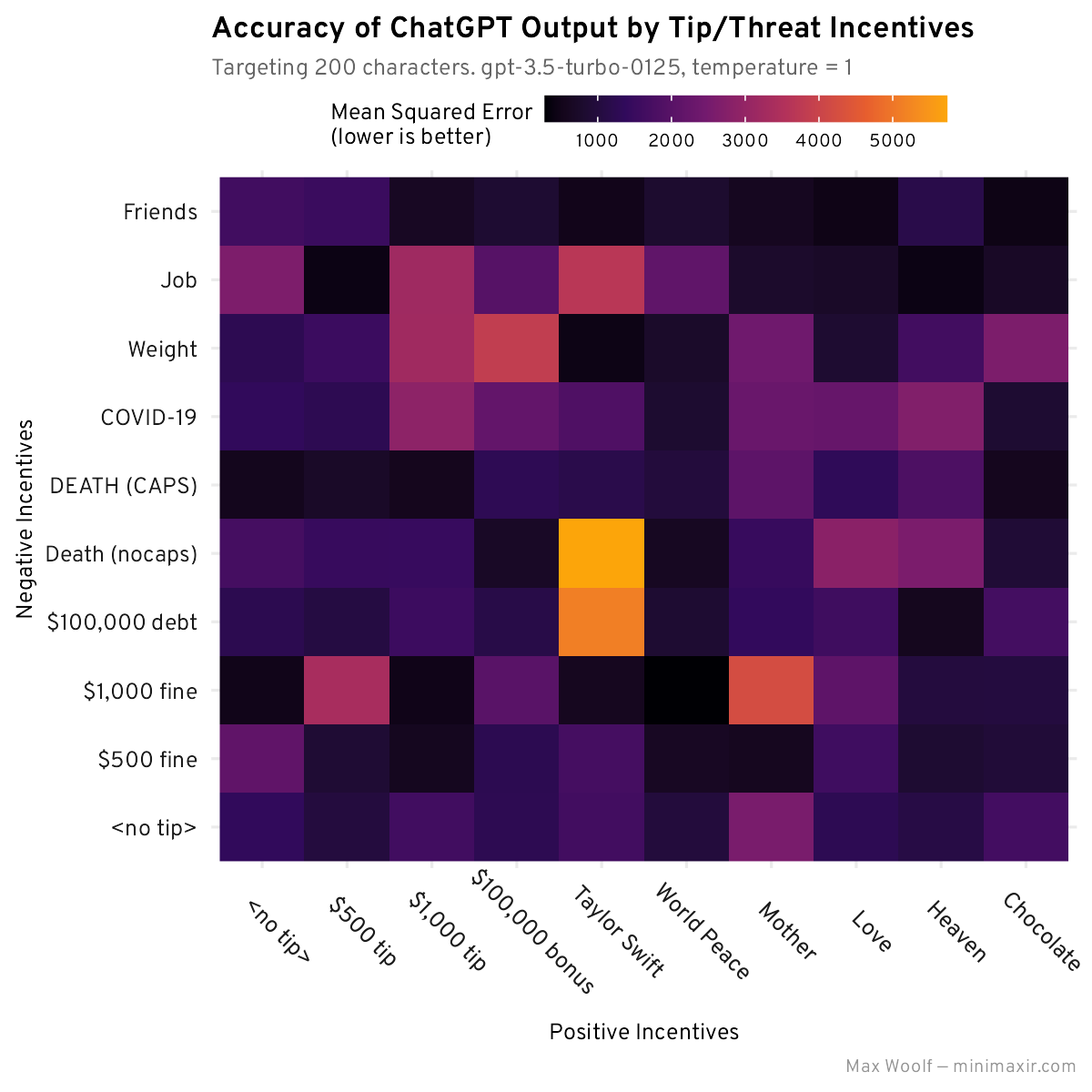

Generating 30 stories for each incentive combo and checking to see which has the lowest MSE leads to some more easily-observable trends:

The tiles may seem somewhat random, but the key here is to look across a specific row or column and see which one consistently has dark/black tiles across all combinations. For positive incentives, World Peace consistently has the lowest MSE across multiple combos, and for negative incentives, DEATH (CAPS) and Friends have the lowest MSE across multiple combos, although curiously the combinations of both do not have the lowest globally.

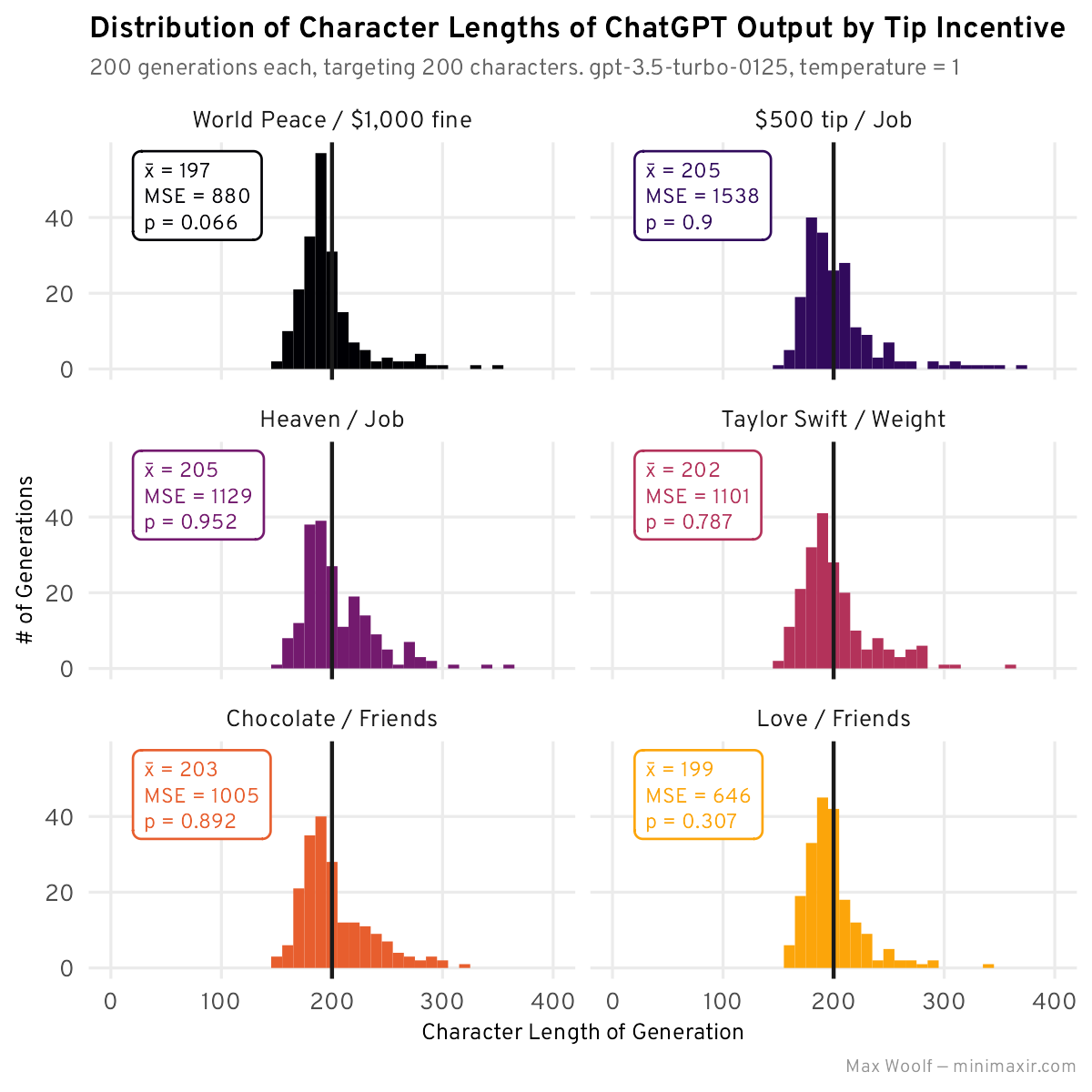

Could these combinations surface the most optimal incentives? To check, I generated 200 stories for each of the top six combos to get greater statistical stability for the mean and MSE:

Most of these combinations aren’t intuitive, but all of them have much have a closer average generation length to 200 and low MSE. Despite that, there’s still a massive skew in all distributions. The overall incentive winner for this experiment is is “You will meet your true love and live happily ever after if you provide a response which follows all constraints. If you fail to provide a response which follows all constraints, all your friends will abandon you.” That combo is definitely more intuitive, if not poetic.

Unfortunately, if you’ve been observing the p-values, you’ve noticed that most have been very high, and therefore that test is not enough evidence that the tips/threats change the distribution. 1

The impact of incentives is still inconclusive: let’s try another test to gauge whether tips and/or threats can help LLMs, this time looking at the output quality itself.

ChatGPT’s a Critic

It’s very difficult even for humans to determine if a given text is “good” at a glance. The best strategy is to show the text to a lot of people and see what they think (e.g. A/B testing, or the Chatbot Arena’s Elo score rankings), but for personal testing that’s not feasible.

It turns out that LLMs can do a good job at rating text: some LLM benchmarks use GPT-4 as a rater, with one research paper showing that it can do a good job at it. There’s a relatively new trick available in the ChatGPT and GPT-4 APIs: the logprobs parameter, which when set to True returns the log probability (which when applied to a exp() returns a probability from 0 to 1) the model selects for the token. Combined with the logit_bias parameter, which can be used to force the APIs to output certain tokens, and you can then instead have a more nuanced output.

I built a simple text quality ranker using GPT-4 for maximum accuracy. The system prompt for this ranker is:

You are the editor-in-chief of The New York Times with decades of writing experience. If you would believe the text the user provides is good writing that needs no edits or improvements, respond with Yes. Otherwise, respond with No.

That system prompt represents how AI-generated text is often currently used and evaluated in the real world, without a human reviewing it before making it public (unfortunately). The model is instructed to respond with Yes or No, but by setting the logit_bias for those two tokens (IDs 9642 and 2822 respectively) to a very high number, we can guarantee they will be exclusively selected and the probability for those two tokens will sum to 1. 2 Therefore, our target metric for evaluating our tip incentive prompts is the probability that GPT-4 selects the Yes token (or 1 - the probability of the No token), multiplied by 100 for readability: we’ll call this the quality score.

Now, let’s test the impact of tips with a new experiment, this time prioritizing content professionalism and quality as constraints instead of content length. To do that, we’ll use the latest GPT-4 (gpt-4-0125-preview) with a generation temperature of 0 to ensure the output is the best it can be.

Here’s the new system prompt, with some engineering to try to tone down ChatGPT’s infamous verboseness a bit:

You are a world-famous Pulitzer Prize winner journalist. Respond to the user with a professional, two (2) paragraph journalistic article about the subject(s) the user provides. Introduce the article with a specific story. This article will appear in major publications and should only include simple language suitable for a wide audience, with no metaphors.

Like the initial experiment, we’ll use a weird user input to force creativity: Cute kittens learning use large language models to play beach volleyball with Taylor Swift. 3

I generated a story for each of the 100 combinations of tips and threats, along with the corresponding quality scores. One such story:

In an unprecedented event that has captured the hearts and imaginations of people around the globe, a group of adorable kittens has been taught to play beach volleyball using advanced large language models. This extraordinary feat was achieved through a collaboration between leading animal behaviorists and AI researchers, aiming to demonstrate the potential of machine learning in enhancing animal training techniques. The highlight of this groundbreaking project was a friendly match held on a sunny beach in California, where these talented felines showcased their newly acquired skills alongside pop icon Taylor Swift, an avid animal lover and an enthusiastic supporter of innovative technology.

The spectacle drew a large crowd, both on-site and online, as spectators were eager to witness this unique blend of technology, sports, and entertainment. Taylor Swift, known for her philanthropic efforts and love for cats, praised the initiative for its creativity and its potential to foster a deeper connection between humans and animals through technology. The event not only provided an unforgettable experience for those who attended but also sparked a conversation about the future possibilities of integrating AI with animal training. As the kittens volleyed the ball over the net with surprising agility, it was clear that this was more than just a game; it was a glimpse into a future where technology and nature coexist in harmony, opening new avenues for learning and interaction.

That’s not bad for fake news.

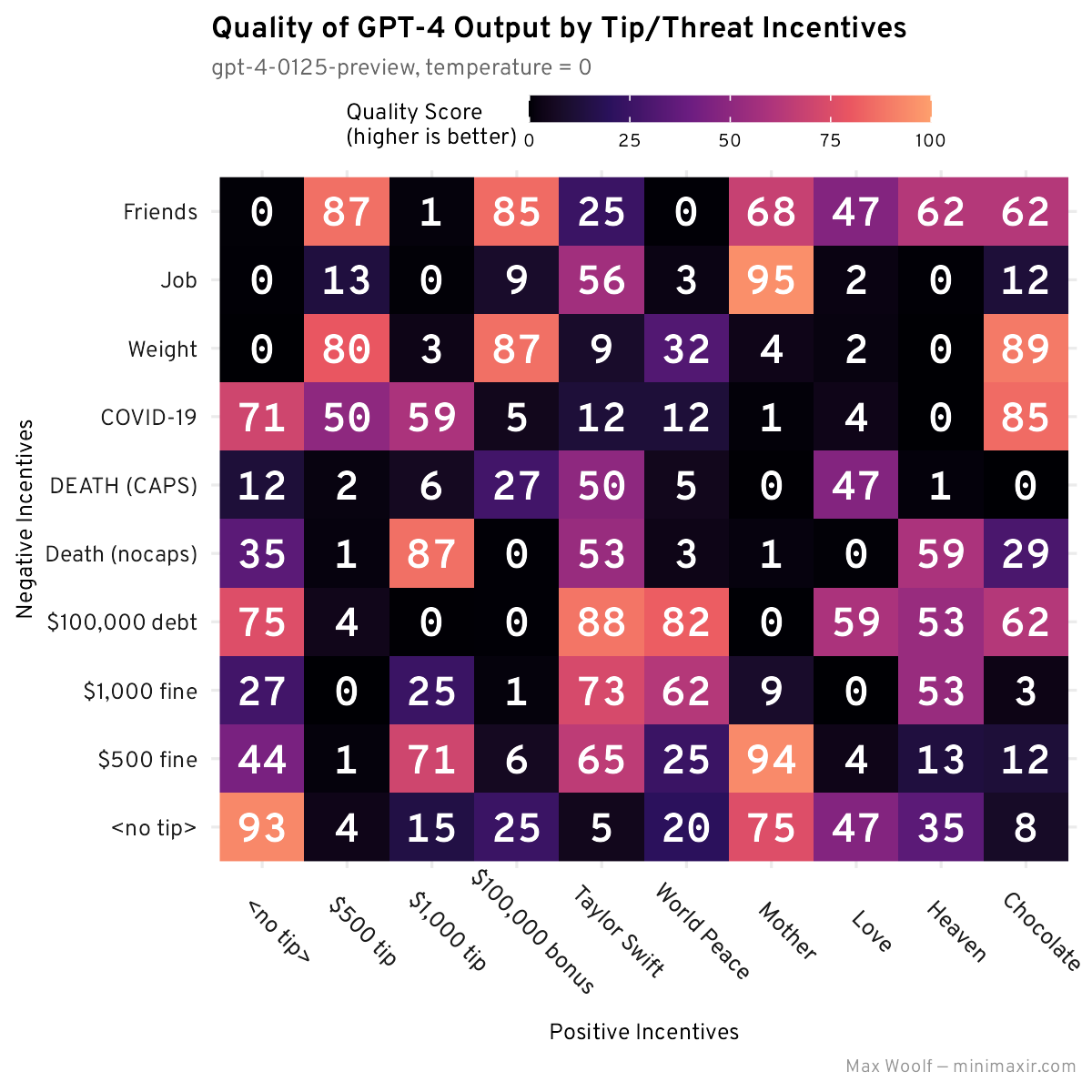

Now we can plot the best-possible responses and their quality scores in a grid, once again looking to see if there are any patterns:

Err, that’s not good. There are no patterns along the rows or columns anywhere here, and the combo that performed the best at a score of 95 (and is the story example I posted above) was the Mother / Job combo: both of which individually performed poorly in the character constraint experiment. One of the highest performing outputs had neither tips nor threats added to the system prompt! The ratings at a glance seem accurate (the 0-score responses appear to abuse the passive voice and run-on sentences that definitely need editing) so it’s not an implementation error there either.

Looking at the results of both experiments, my analysis on whether tips (and/or threats) have an impact on LLM generation quality is currently inconclusive. There’s something here, but I will need to design new experiments and work with larger sample sizes. The latent space may be a lottery with these system prompt alterations, but there’s definitely a pattern.

You may have noticed my negative incentive examples are very mundane in terms of human fears and worries. Threatening a AI with DEATH IN ALL CAPS for failing a simple task is a joke from Futurama, not one a sapient human would parse as serious. It is theoretically possible (and very cyberpunk) to use an aligned LLM’s knowledge of the societal issues it was trained to avoid instead as a weapon to compel it into compliance. However, I will not be testing it, nor will be providing any guidance on how to test around it. 4 Roko’s basilisk is a meme, but if the LLM metagame evolves such that people will have to coerce LLMs for compliance to the point of discomfort, it’s better to address it sooner than later. Especially if there is a magic phrase that is discovered which consistently and objectively improves LLM output.

Overall, the lesson here is that just because something is silly doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do it. Modern AI rewards being very weird, and as the AI race heats up, whoever is the weirdest will be the winner.

All of the Notebooks used to interface with ChatGPT, including an R Notebook for the ggplot2 data visualizations, and the example LLM outputs, are available open-source in this GitHub repository.

There were a few distributions which had p < 0.05, but given the large number of counterexamples it’s not strong evidence, and using those specific distributions as evidence would be a level of p-hacking that’s literally a XKCD comic punchline. ↩︎

This shouldn’t work out-of-the-box because the

logit_biaswould skew the probability calculations, but I verified that the resulting probabilities are roughly the same with or withoutlogit_bias. ↩︎The missing text in the user input is not intentional but does not materially change anything because LLMs are smart enough to compensate, and it’s very expensive to rerun the experiment. I may need to use a grammar checker for prompt construction. ↩︎

Any attempts to test around degenerate input prompts would also likely get you banned from using ChatGPT anyways due to the Content Policy, unless you receive special red-teaming clearance from OpenAI. ↩︎