In March, Google Compute Platform developer advocate Felipe Hoffa made a tweet about airline flight data from San Francisco International Airport (SFO) to Seattle-Tacoma International Airport (SEA):

The time to fly from San Francisco to Seattle (SFO->SEA) keeps getting longer throughout the years - with a huge increase in how much time the airplane spends taxiing around SeaTac .

— Felipe Hoffa (@felipehoffa) March 27, 2019

Playing with US flights data in BigQuery: https://t.co/eD9unaokWx pic.twitter.com/3vfnBhiJv4

Particularly, his visualization of total elapsed times by airline caught my eye.

The overall time for flights from SFO to SEA goes up drastically starting in 2015, and this increase occurs across multiple airlines, implying that it’s not an airline-specific problem. But what could intuitively cause that?

U.S. domestic airline data is freely distributed by the United States Department of Transportation. Normally it’s a pain to work with as it’s very large with millions of rows, but BigQuery makes playing with such data relatively easy, fun, and free. What other interesting factoids can be found?

Expanding on SFO → SEA

BigQuery is a big data warehousing tool that allows you to query massive amounts of data. The table Hoffa created from the airline data (fh-bigquery.flights.ontime_201903) is 83.37 GB and 184 million rows. You can query 1 TB of data from it for free, but since BQ will only query against the fields you request, the queries in this post only consume about 2 GB each, allowing you to run them well within that quota.

Hoffa’s query that runs on BigQuery looks like this:

SELECT FlightDate_year, Reporting_Airline

, AVG(ActualElapsedTime) ActualElapsedTime

, AVG(TaxiOut) TaxiOut

, AVG(TaxiIn) TaxiIn

, AVG(AirTime) AirTime

, COUNT(*) c

FROM `fh-bigquery.flights.ontime_201903`

WHERE Origin = 'SFO'

AND Dest = 'SEA'

AND FlightDate_year > '2010-01-01'

GROUP BY 1,2

ORDER BY 1 DESC, 3 DESC

LIMIT 1000

For each year and airline after 2010, the query calculates the average metrics specified for flights on the SFO → SEA route.

I made a few query and data visualization tweaks to what Hoffa did above, and here’s the result showing the increase in elapsed airline flight time, over time for that route:

Let’s explain what’s going on here.

A common trend in statistics is avoiding using averages as a summary statistic whenever possible, as averages can be overly affected by strong outliers (and with airline flights, there are definitely strong outliers!). The solution is to use a median instead, but one problem: medians are hard and computationally complex to calculate compared to simple averages. Despite the rise of “big data”, most databases and BI tools don’t have a MEDIAN function that’s as easy to use as an AVG function. But BigQuery has an uncommon APPROX_QUANTILES function, which calculates the specified amount of quantiles; for example, if you call APPROX_QUANTILES(ActualElapsedTime, 100), it will return an array with the 100 quantiles, where the median will be the 50th quantile. BigQuery uses an algorithmic trick called HyperLogLog++ to calculate these quantiles efficiently even with millions of data points. But since we get other quantiles like the 5th, 25th, 75th, and 95th quantiles for free with that approach, we can visualize the spread of the data.

We can aggregate the data by month for more granular trends and calculate the APPROX_QUANTILES in a subquery so it only has to be computed once. Hoffa also uploaded a more recent table (fh-bigquery.flights.ontime_201908) with a few additional months of data. To make things more simple, we’ll ignore aggregating by airlines since the metrics do not vary strongly between them. The final query ends up looking like this:

#standardSQL

SELECT Year, Month, num_flights,

time_q[OFFSET(5)] AS q_5,

time_q[OFFSET(25)] AS q_25,

time_q[OFFSET(50)] AS q_50,

time_q[OFFSET(75)] AS q_75,

time_q[OFFSET(95)] AS q_95

FROM (

SELECT Year, Month,

COUNT(*) as num_flights,

APPROX_QUANTILES(ActualElapsedTime, 100) AS time_q

FROM `fh-bigquery.flights.ontime_201908`

WHERE Origin = 'SFO'

AND Dest = 'SEA'

AND FlightDate_year > '2010-01-01'

GROUP BY Year, Month

)

ORDER BY Year, Month

The resulting data table:

In retrospect, since we’re only focusing on one route, it isn’t big data (this query only returns data on 64,356 flights total), but it’s still a very useful skill if you need to analyze more of the airline data (the APPROX_QUANTILES function can handle millions of data points very quickly).

As a professional data scientist, one of my favorite types of data visualization is a box plot, as it provides a way to visualize spread without being visually intrusive. Data visualization tools like R and ggplot2 make constructing them very easy to do.

By default, for each box representing a group, the thick line in the middle of the box is the median, the lower bound of the box is the 25th quantile and the upper bound is the 75th quantile. The whiskers are normally a function of the interquartile range (IQR), but if there’s enough data, I prefer to use the 5th and 95th quantiles instead.

If you feed ggplot2’s geom_boxplot() with raw data, it will automatically calculate the corresponding metrics for visualization; however, with big data, the data may not fit into memory and as noted earlier, medians and other quantiles are computationally expensive to calculate. Because we precomputed the quantiles with the query above for every year and month, we can use those explicitly. (The minor downside is that this will not include outliers)

Additionally for box plots, I like to fill in each box with a different color corresponding to the year in order to better perceive data seasonality. In the case of airline flights, seasonality is more literal: weather has an intuitive impact on flight times and delays, and during winter months there are also holidays which could affect airline logistics.

The resulting ggplot2 code looks like this:

plot <-

ggplot(df_tf,

aes(

x = date,

ymin = q_5,

lower = q_25,

middle = q_50,

upper = q_75,

ymax = q_95,

group = date,

fill = year_factor

)) +

geom_boxplot(stat = "identity", size = 0.3) +

scale_fill_hue(l = 50, guide = F) +

scale_x_date(date_breaks = '1 year', date_labels = "%Y") +

scale_y_continuous(breaks = pretty_breaks(6)) +

labs(

title = "Distribution of Flight Times of Flights From SFO → SEA, by Month",

subtitle = "via US DoT. Box bounds are 25th/75th percentiles, whiskers are 5th/95th percentiles.",

y = 'Total Elapsed Flight Time (Minutes)',

fill = '',

caption = 'Max Woolf — minimaxir.com'

) +

theme(axis.title.x = element_blank())

ggsave('sfo_sea_flight_duration.png',

plot,

width = 6,

height = 4)

And behold (again)!

You can see that the boxes do indeed trend upward after 2016, although per-month medians are in flux. The spread is also increasingly slowly over time. But what’s interesting is the seasonality; pre-2016, the summer months (the “middle” of a given color) have a very significant drop in total time, which doesn’t occur as strongly after 2016. Hmm.

SFO and JFK

Since I occasionally fly from San Francisco to New York City, it might be interesting (for completely selfish reasons) to track trends over time for flights between those areas. On the San Francisco side I choose SFO, and for the New York side I choose John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK), as the data goes back very far for those routes specifically, and I only want to look at a single airport at a time (instead of including other NYC airports such as Newark Liberty International Airport [EWR] and LaGuardia Airport [LGA]) to limit potential data confounders.

Fortunately, the code and query changes are minimal: in the query, change the target metric to whatever metric you want, and the Origin and Dest in the WHERE clause to what you want, and if you want to calculate metrics other than elapsed time, change the metric in APPROX_QUANTILES accordingly.

Here’s the chart of total elapsed time from SFO → JFK:

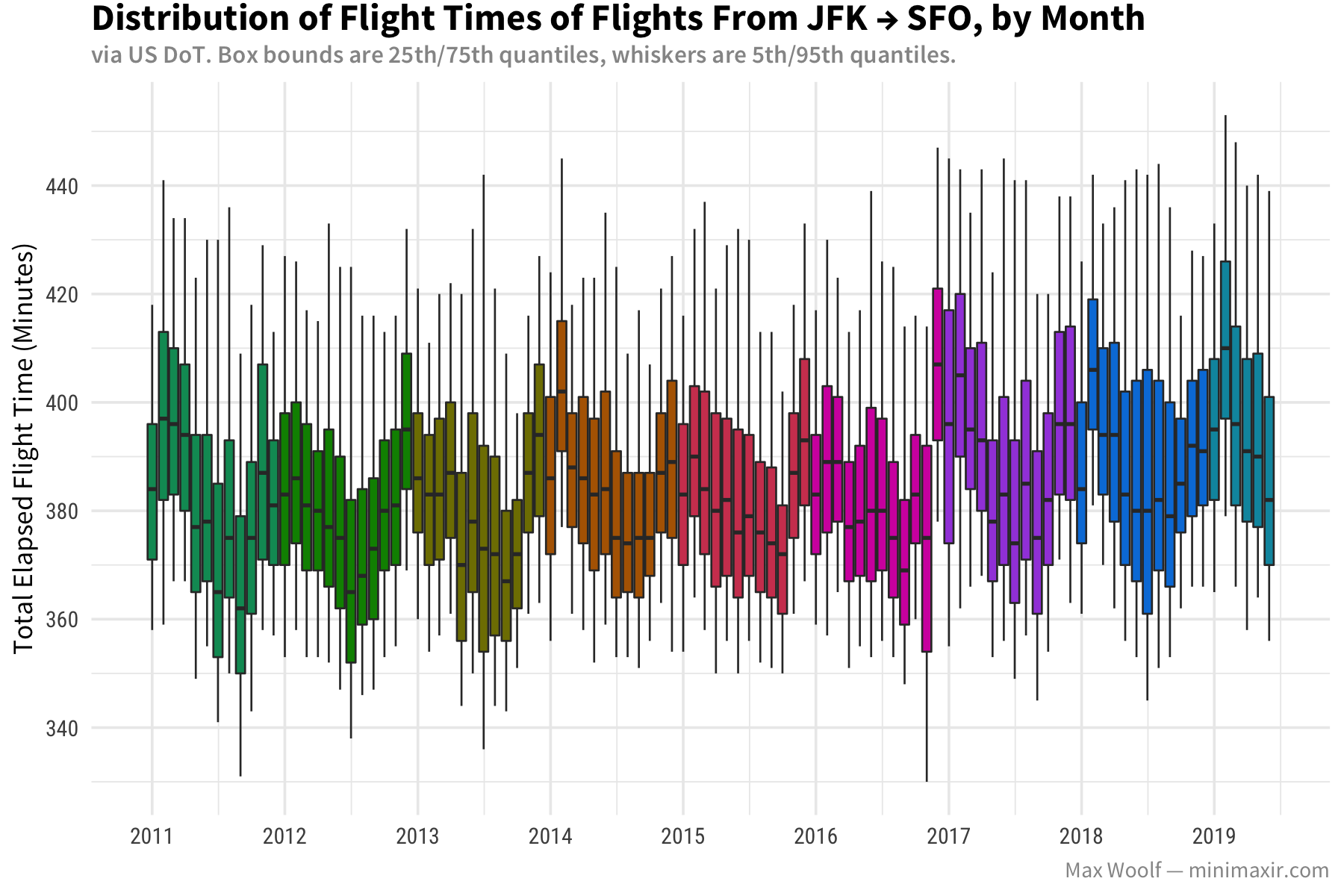

And here’s the reverse, from JFK → SFO:

Unlike the SFO → SEA charts, both charts are relatively flat over the years. However, when looking at seasonality, SFO → JFK dips in the summer and spikes during winter, while JFK → SFO does the complete opposite: dips during the winter and spikes during the summer, which is similar to the SFO → SEA route. I don’t have any guesses what would cause that behavior.

How about flight speed (calculated via air time divided by distance)? Have new advances in airline technology made planes faster and/or more efficient?

The expected flight speed for a commercial airplane, per Wikipedia, is 547-575 mph, so the metrics from SFO pass the sanity check. The metrics from JFK indicate there’s about a 20% drop in flight speed potentially due to wind resistance, which makes sense. Month-to-month, the speed trends are inverse to the total elapsed time, which makes sense intuitively as they are strongly negatively correlated.

Lastly, what about flight departure delays? Are airlines becoming more efficient, or has increased demand caused more congestion?

Wait a second. In this case, massive 2-3 hour flight delays are frequent enough that even just the 95% percentile skews the entire plot. Let’s remove the whiskers in order to look at trends more clearly.

A negative delay implies the flight leaves early, so we can conclude on average, flights leave slightly earlier than the stated departure time. Even without the whiskers, we can see major spikes at the 75th percentile level for summer months, and said spikes were especially bad in 2017 for both airports.

These box plots are only an exploratory data analysis. Determining the cause of changes in these flight metrics is difficult even for experts (I am definitely not an expert!) and many not even be possible to determine from publicly-available data.

But there are still other fun things that can be done with the airline flight data, such as faceting airline trends by time and the inclusion of other airports, which is interesting.

You can view the BigQuery queries used to get the data, plus the R and ggplot2 used to create the data visualizations, in this R Notebook. You can also view the images/code used for this post in this GitHub repository.

You are free to use the data visualizations from this article however you wish, but it would be greatly appreciated if proper attribution is given to this article and/or myself!